Lucia Pizzani (b. 1975, Caracas, Venezuela) lives and works in London. Pizzani’s expressive practice involves the body and self always informed by materiality. One of her core concerns is the interrelationship between narratives of women in history and processes of metamorphosis in the natural world. She works across a variety of media – including photography, ceramics, videos, drawings, performances and installations. Having worked as part of the environmental movement in Venezuela for many years, she has always incorporated ecological elements into her artwork. Born in Caracas, lives and works in London, she graduated from Chelsea College of Art and Design and also studied Conservation Biology at the Columbia University in New York. Her work has recently been incorporated to the TATE Collection and recent commissions and residencies include Launch Pad Lab, Casa Wabi and The Cultivist. She was the recipient of the “Premio Eugenio Mendoza” (Mendoza Foundation National Award) in Venezuela in 2013.

Pizzani’s physical environment often provides her with both the inspiration and physical materials, for her work. This has had particular importance during recent artists in residencies she has done abroad. The traveling and sense of misplaced have been part of her life since an early age, while she bounced between Europe, North America, and her home country. In the last years, from her London studio, she combines materials and stories from different territories trying to reconcile that distance. Her research and production are often hybrid, syncretic, and with no defined temporality, allowing the works to have multi-layered readings.

The founding director of Open Space and curator of Transient Roots Huma Kabakci interviews Lucia on her practice, her recent body of work, and her experience in previous residencies.

You were born in Venezuela but now live and work in London. When did you move to the UK?

I moved here in 2007 and did my Masters in Fine Arts at Chelsea College in 2008 and 2009. During the first half of these 15 years here, I was back and forward to Venezuela as I was exhibiting and producing works there. I participated in important shows such as the National Award Premio Mendoza in which I received 1st prize and that took me to my first ever artist in residency: Hangar in Barcelona. In the second half of this time, I haven’t been able to go back as the situation in Venezuela turned for the worst with crazy crime rates, electric cuts, and scarcity of food and medicines amongst other things. This summer I’m traveling back after six years for a survey show at an Art Centre there and to see family.

You work with a number of mediums that include photography, ceramics, videos, drawings, performances, and installations. How do you navigate your preferred medium for a new series/work of art?

I follow a research process, I make in the same way that l think and feel, and it’s a holistic view where it’s difficult to think of mediums as separate entities. The time dedicated to mastering a way of making will of course be noticeable in the outcome. I started with photography when I was fifteen, then studied for a BA in visual communications (BAs in Venezuela are 5 years long) then I did lots of videos, photography, and other visual projects. Then at Chelsea College, I started full on with Ceramics which I haven’t stopped since then, that makes 14 years dedicated to that medium. I can’t choose between mediums as I feel they are all part of myself, It would be like choosing between an arm or a leg.

You have taken part in a number of international residencies. Can you name your favourite experiences and why?

Each experience is different, being in a rural site has many positives as you feel nourished from the natural setting, and you can focus 100% on the research and work, such as the fabulous time I had in LaunchPad Lab in France two years ago, although for some it can feel isolated as well. I have also been to cities like Barcelona at Hangar or Ciudad de México with Fundación Marso where you meet lots of new people and get involved with the local art scene and projects. But my most recent residency, Casa Wabi on the Oaxacan coast of Mexico, was particularly special and I still cherish the time there. The overwhelming nature interacting with the architecture by Tadao Ando made it very surreal. Extreme beauty all around, crazy flora and fauna, and colours almost fluorescent, actually bioluminescent as we could swim amongst these organisms in the local lagoon. And while living in that environment I was working on producing a sculpture installation for the Botanical Garden of Puerto Escondido about local medicinal and edible plants. Using clay directly from the local pit, working with the maestro alfarero (master potter, ceramicist) and also the welder’s workshop that was run by a family who also did an amazing job putting together the structures of the sculptures.

A group of 9 sculptures of clay and steel was installed permanently at the Puerto Escondido Botanical Garden.

You are one of the participating artists in the exhibition Transient Roots at Sapling Gallery. Can you tell me about your involvement and the works in the exhibition?

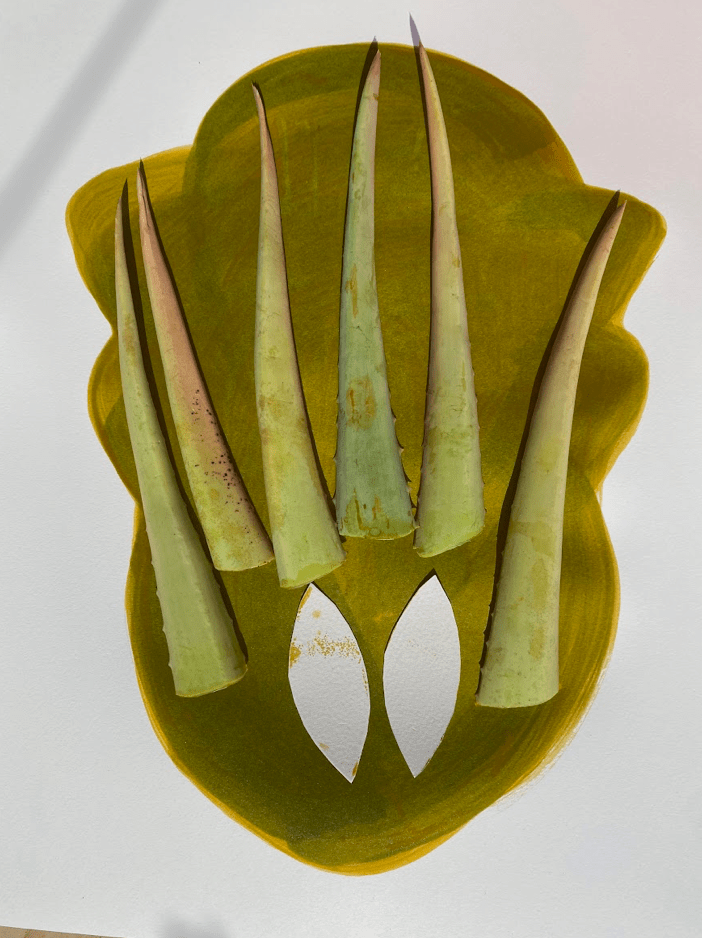

The works on view are at the soul of this exhibition as they are made or imprinted by plants. Also they are a mix of places and territories, the black stoneware ceramics are made with english clay but imprinted with corn and Tabachin seed pods from Mexico. They are anthropomorphic beings, hybrids between humans and plants.

The Solar prints were done in Tenerife, where my family migrated a few years ago, the plants I used are migrants too. Many come from Africa, others from America, and others are local. I fixed the images with the sun rays, as I use photosensitive inks, and that is why I made this happen on Solstice day, as an homage to the Sun. The first time I did Solar prints like this was in Casa Wabi, during the summer solstice. I think these conversations started when you came to my studio a few months ago, and with time the project started to develop and take that direction also after a dialogue with Vanessa’s work.

Clay plays a significant factor in your artistic practice, whether imprinting, tracing, embodying, or transforming it by exploring gender, body, and nature issues. You imprint corn or other vegetal beings onto clay that can be transmitted to paper as clay drawings. What is the relationship between clay and the body? Do you use the clay as a metaphor for the skin or a shell?

There is a historical relation between clay and the body through creational myths in different cultures, and, of course, it was used as the material to make tools for cooking and domestic use for thousands of years now. There is a Mayan myth that tells a story of how we were created by the gods, and the first humans were made of clay. They didn’t survive, so the gods used wood and failed too; finally, they were made of corn. That made them feel and think and could now populate the Earth, teaching their children to care for nature and plant the land, and they thrived.

The first expressions of material culture were found on clay objects, and many of the first amulets and figures and idols, such as venuses, were too. That relationship is super direct as it’s our soil, where plants grow, where we step on, that is, the material, an ancient one, always present and manipulated in many ways over time.

I experienced the whole process from taking the mud from a pit and digging on the ground to then cleaning it from rocks and roots and using it by sculpting and firing it on a traditional hand-built, open-air brick kiln in Oaxaca during the residency at Casa Wabi.

And I realised you hadn’t used glazing in the ceramics you have produced at Casa Wabi residency, which gives a more natural feel and texture to the clay as well. When did you transition from glazing to non-glazing in your firing technique?

Yes, there has been a progression to “undress” the sculptures. I started using only a bit of glaze on very fleshy works back in 2008, and then I moved to multiple layers of glazes that melted together in the kiln. But I came back to a more minimal use of glaze, and for the past three years, my clay has been naked. I’m very much interested in the natural pigmentation of the clay itself and how that relates to its origin.

The coloration of the terracotta in Oaxaca is different from the one available in London. The process of Mexican black clay is unique and has to do with an ancient way to fire and sanding the pieces. I saw it when I visited San Bortolo Coyotepec. The black clay I have used in the UK is prepared with a high concentration of iron, while the tone of the one I found in Limoge when working at the LaunchPad Lab residency was also different. There I developed a new series of clay drawings on paper where all these pigmentations can be appreciated.

Going back to the relationship with the body, I just want to add that in my ceramics, clay has become a second skin, textured in a way that resembles a reptile. I have covered my body with raw clay for video performance, made wearable pieces in terracotta, and photographed boldly-looking pieces on my skin, so the interconnection is recurrent.

It is funny how certain ingredients or vegetables can be interpreted or used in different contexts based on the country. Totally, it resembles a snake or the skin of corn. Speaking of corn, you also use imprinting of corn on clay, and corn plays a significant part in Mexican and Venezuelan culture. For me, corn has a special childhood memory. In Istanbul, the street vendors would go around with a cart by the Bosphorus and sell corn on the cobs gently poached in water and milk with sugar and butter served warm with salt flakes. I still remember the taste and texture vividly, smiling like a kid…

Your projects are mostly research-based and incorporate different mediums, which feed into another. Can you elaborate on how all these mediums feed into your artistic practice but also previous studies in Visual Communication, Conservation Biology, and Fine Arts?

I’m drawn to stories; exploring the past makes me rethink our current, most basic philosophical inquiries.

I definitely see the story-telling aspect of your work, but your practice is also very research-heavy and based on visual documentation.

The training as a journalist, when studying visual communications, gave me tools for research and writing that are part of my practice and that I applied when working for an environmental organization in Venezuela for many years. I went more in-depth when I studied at Columbia University for a certificate in Conservation Biology, and that strong interest in the planet and its species is still very present in my work as an artist.

Some examples are a project on the Suffragettes’ attack on the Orchids’ house in Kew Gardens (2011) and the ambiguity of the origin of the flower’s name (it means testicle in greek) another on Beatrix Potter’s findings on Fungi spore reproduction (2015) in a time where women were not allowed to take part in science, and in The Worshipper of the Image (2013), I made a video and collodion wet plates with textile cocoon suits/sculptures responding to metamorphosis in butterflies as a mean of transformation and liberation, that are now part of the Tate collection.

The variety of mediums is a freedom that comes naturally to me, as when you speak and use different words as part of your language. Having said that, I do believe in dedicating time to learning the specificity of different metiers, and I consider myself a maker. I have been working with ceramics for many years, attending courses, and am always open to trying new gazes, bodies of clay, or techniques for building. Photography has been a passion too since I was a teenager. I was raised by a family of artists in a booming Caracas in the 80s, attending museum and gallery shows regularly, participating in my mother’s video art pieces, and roaming around huge paintings in my father’s studio.

The symbol of the serpent or the spiral in your practice is a recurring theme, what does this use of symbolism really mean and what role does it play?

Around 6 years ago I started researching the snake after producing the first ceramics with black glaze and reptile texture. I named the series “Cuaima” which is one of the most poisonous snakes in Venezuela, but it’s also a pejorative nickname for women there. For me, it reflects the strength our matriarchal society has in spite of the machismo there. It’s also about the resilience women have had throughout the acute crisis the country is going through by finding ways to provide for their families.

The snake is by far the most extensive symbolic animal in regards to all the meanings, legends, myths, and stories associated with it, many of them creational ones and across time and cultures. This reptile embodies regeneration and healing as it moults its skin visibly, so it also coincides with this idea of a second skin I have been working with.

When I visited the Lascaux Caves and read texts about the snake’s symbolic meaning in prehistoric times, it was related to fertility, connected to the underworld waters that were like an amniotic liquid in the womb. And in my many visits and stays in Mexico, I have seen it everywhere. As the winged god Quetzalcoatl and in other forms too. The curled one, like an Ouroboros that stands for the cycles in life and history, biting its own tail, and in the shape of a spiral that was one of the primal symbols drawn on caves.